GAO: EPA Relies on Outdated Systems to Manage Air Quality Data

Two IT air quality data systems that inform the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA’s) regulatory and compliance decisions are outdated, the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) has suggested. The federal agency must make progress to develop a business case to replace them, it said.

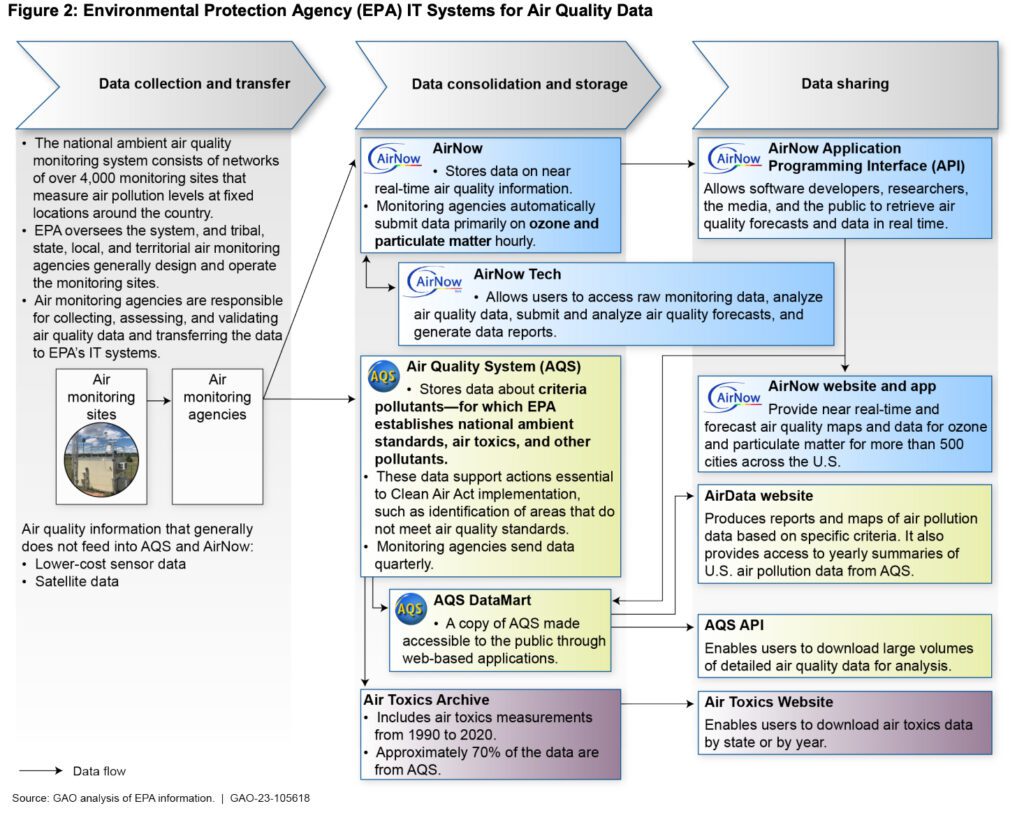

The congressional watchdog in a report made public on Sept. 29 noted the EPA primarily relies on two legacy systems—the Air Quality System (AQS) and the AirNow system—to manage and report air quality data collected through the national ambient air quality monitoring system. “The data inform regulatory and compliance decisions that have associated economic impacts totaling billions of dollars, including the costs of reducing air pollution and the benefits associated with reducing adverse health effects from poor air quality,” the GAO said.

However, the “age and design” of the EPA’s AQS and AirNow systems “can be difficult to maintain, access, and use.” That “limits their functionality and poses resource and other challenges” for the federal environmental agency, monitoring agencies, and other data users, it said. While the GAO had previously reported concerns about the AQS, and the EPA moved to make the IT system one of its top three “mission-critical systems in need of modernization,” progress remains limited, it said.

Legacy System Data a Cornerstone for EPA’s Regulatory, Compliance Efforts

Under the amended Clean Air Act of 1970, the EPA regulates several air pollutants. Among these are “criteria” pollutants, a set of six common pollutants—carbon monoxide, lead, ozone, particulate matter (PM), nitrogen dioxide, and sulfur dioxide—that are emitted by power plants, other industrial sources, and vehicles.

The EPA regulates these pollutants by setting “allowable” levels under National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS). The Clean Air Act requires the agency to review NAAQS every five years and revise them if appropriate. Ozone NAAQS, for example, are a primary feature in the EPA’s controversial Good Neighbor Plan, a March 15–finalized rule that the agency suggested could result in an additional 14 GW of coal retirements nationwide.

Another air pollutant category, known as “hazardous air pollutants (HAPs)”—and more commonly, “air toxics”—spans 188 pollutants that could pose health risks in small quantities. These include mercury emissions from power plants and benzene from gasoline. The EPA’s Mercury and Air Toxics Standards (MATS), for example, set limits on power plant HAP emissions. In April, notably, it proposed to considerably tighten the MATS, with specific repercussions for coal- and oil-fired generation.

The EPA collects most pollutant emissions data from regulated power plant sources, which monitor, measure, and report emissions via continuous emission monitoring systems (CEMS) or sorbent traps (for mercury), though some units with low emissions may conduct periodic stack tests in lieu of continuous monitoring.

But, under the Clean Air Act, states and territories are generally responsible for managing air quality in their jurisdictions, including by establishing State Implementation Plans (SIPs) that describe how each state will attain and maintain compliance with the NAAQS. To determine NAAQS compliance, state and local governments operate air quality monitors that are part of a national ambient air monitoring system to measure air pollution levels. (Ambient air means the portion of the atmosphere outside buildings to which the public has access.)

The national system, which includes monitors located at more than 4,000 fixed-location monitoring sites, “provides standardized information essential for implementing the Clean Air Act and protecting public health,” the GAO says. The EPA, in turn, uses two legacy IT systems—AQS and AirNow—to manage and report air quality data collected through the national ambient air quality monitoring system.

Air Quality Data Managed Through Two Legacy Systems: AQS and AirNow

AQS, developed and implemented in 1996, is the EPA’s “repository” for ambient air quality data about criteria pollutants. That data, sent to the EPA by 128 monitoring agencies, supports “actions essential to Clean Air Act implementation, such as identification of areas that do not meet air quality standards,” the GAO said.

“Monitoring agencies are required to report data to AQS quarterly, take quality assurance steps to verify and validate their data, and annually certify that the data they submit to AQS are complete and accurate to the best of their knowledge,” the agency noted. “EPA uses AQS as its long-term repository of regulatory ambient air quality data, according to EPA documents.” The data is made public through the EPA’s AirData website

AirNow, developed and implemented in the late 1990s receives and stores “near real-time” data primarily on ozone and particulate matter. Monitoring agencies automatically submit data primarily on ozone and PM hourly. AirNow also allows users to access raw monitoring data that organizations use to evaluate daily health risks. “AirNow is programmed to perform preliminary data quality assessments,” the GAO noted. “However, unlike the data submitted to AQS, the data submitted to AirNow are not certified as complete and accurate. This is because AirNow data are not used for regulatory purposes and, instead, are used to provide the public with near real-time information.”

Age and Design of AQS Present ‘Maintenance and Usability Challenges’

While the EPA has established internal processes for management and oversight of the agency’s IT systems, “due to their age and design, AQS and AirNow can be difficult to maintain, access, and use, according to our analysis of EPA and stakeholder views,” the GAO said.

While AQS prominently uses an Oracle database and Oracle Forms and Reports, Oracle announced that it will cease supporting Oracle Reports in September 2023. The EPA is now “working with a contractor to transition to a different software for AQS reports,” the report notes.

However, the aging system can also present “technological and staffing challenges for both EPA and monitoring agencies,” the watchdog noted. For example, EPA told the GAO that as of January 2023, there was “one person at EPA who had been working on AQS for more than a year. In addition, AQS has accumulated extensive amounts of code over time, which has made the system increasingly susceptible to bugs when EPA officials attempt to make changes to the system, according to EPA officials.”

The legacy system is also proving costly to maintain. “EPA pays license fees for legacy data storage, which is more costly than cloud-based storage.” That’s precarious because the quantity of AQS’s air quality data has “grown significantly,” as regulations evolve and with the shift to digital data. And, as the amount of data in AQS increases, the cost of data storage has increased. “Further potential increases in data, such as from increases in continuous monitoring across a wider range of pollutants, would create substantially more data to manage.”

The outdated software, notably, also poses new difficulties in keeping the system “up to date” with monitoring information and regulatory and security updates. “In particular, EPA officials said that they must devote much of their time to fixing existing problems in order to keep AQS functional for users, allowing little time to update the system with regulatory and other changes. According to monitoring agency officials, it can take years for AQS to reflect regulatory requirements or national guidance for monitoring.” As significantly, the outdated AQS software can “complicate efforts” to access and analyze air quality data,” it said.

Among the EPA’s biggest challenges is that it must manage separate systems—AQS, AirNow, and the AirToxics Archive—posing inefficient use of resources and potential confusion for users. That’s proving especially cumbersome as the EPA grapples with finding and retaining IT staff with the knowledge to support its legacy systems.

A Mission-Critical Task

Recognizing these challenges, the EPA has for the past five years explored replacing AQS and AirNow with a new “single IT system.” In 2017, the GAO notes, “EPA’s acting CIO listed AQS as one of EPA’s top three mission-critical systems in need of modernization.”

However, the EPA has “not clearly identified AQS and AirNow” as candidates for replacement through its IT management and oversight processes that are intended to ensure that the systems effectively support the agency’s mission and strategic goals. Furthermore, EPA has not documented a business case to secure management approval for a new system.” These gaps are partially driven by the EPA’s “competing priorities and resource limitations,” the report suggests.

“Officials from EPA’s air office stated that they are working on the tasks needed to develop the business case for the new system. Specifically, the agency is working to document the vision for the new system, including the scope, time frame, and estimated cost,” it added. “Officials from EPA’s air office stated that they will use this information as part of their business case to request management approval for funding to develop the new system.”

Still, according to the report, the EPA has made some gains in developing air quality monitoring modernization. The EPA told the GAO that to date, the agency has used appropriations from the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 and the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 to award $53.4 million to enhance air quality monitoring in 37 states, and nearly $22.5 million to tribal, state, and local agencies for “enhanced monitoring” of criteria pollutants.

—Sonal Patel is a POWER senior associate editor (@sonalcpatel, @POWERmagazine).