How Westinghouse, Symbol of U.S. Nuclear Power, Collapsed

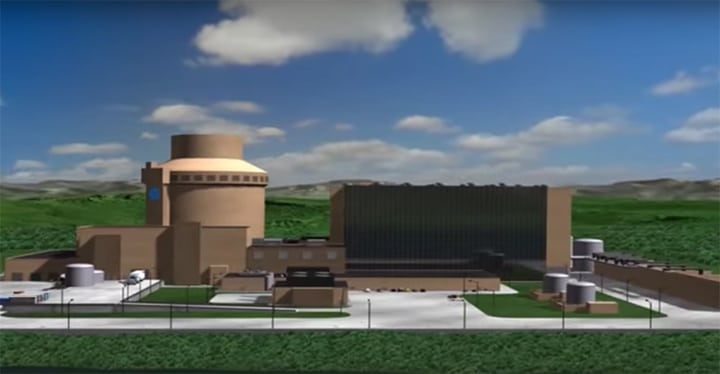

Crippled by financial setbacks stemming from the half-built AP1000 reactor projects in Georgia and South Carolina, Westinghouse Electric Co., a company with a storied legacy symbolic of American nuclear power, has taken the desperate step of filing for bankruptcy protection.

While owners of the two nuclear construction projects are monitoring the situation, the development could mean their completion is uncertain.

The U.S. company owned by Japan’s Toshiba Corp. on March 29 filed for voluntary petitions under Chapter 11 of the U.S. Bankruptcy Code, saying it is seeking to undertake “a strategic restructuring as a result of certain financial and construction challenges in its U.S. AP1000 power plant projects.”

The company said it has obtained $800 million in debtor-in-possession financing from a third-party lender to help fund and protect its core businesses during its reorganization. The financing is expected to fund Westinghouse’s “strong” business units relating to plant operation, nuclear fuel, and components manufacturing and engineering, as well as decommissioning, decontamination, remediation, and waste management.

“Today, we have taken action to put Westinghouse on a path to resolve our AP1000 financial challenges while protecting our core businesses,” said Westinghouse’s Interim President and CEO José Emeterio Gutiérrez.

“We are focused on developing a plan of reorganization to emerge from Chapter 11 as a stronger company while continuing to be a global nuclear technology leader.”

Weak at the Knees

Westinghouse’s bankruptcy protection filing has been anticipated for some time. Global technology conglomerate Toshiba Corp. in mid-February reported it would write off more than $6 billion and withdraw from the business of building new nuclear power plants, citing spiraling cost overruns at projects to build new flagship AP1000 reactors at Plant Vogtle in Georgia and Virgil C. Summer Nuclear Station in South Carolina.

According to Westinghouse, the losses are specifically rooted in its construction business, which is divided into two segments: engineering, procurement, and construction (EPC) services, primarily offering the AP1000 technology; and engineering and procurement.

“While some portions of the Construction Business are profitable, the main portion of the EPC business, which constructs the Vogtle and VC Summer projects, has damaged the profitability of the entire Construction Business,” Westinghouse said in its filing on March 29. “As a result, the Construction Business generated [earnings before interest, tax, depreciation, and amortization] from FY2013 to FY2015 of negative $343 million,” it said (company’s emphasis).

Progress at both projects has been impaired by costly delays. Plant Vogtle Units 3 and 4, which were certified by the Georgia Public Service Commission in March 2009 at $14.3 billion is more than $3 billion over budget. Oglethrope Power Corp., a power supply cooperative that owns the project along with Georgia Power, Municipal Electric Authority of Georgia, and the City of Dalton Utilities, in a March 27 financial filing said that the latest completion deadlines (supplied by Westinghouse) of December 2019 and September 2020—already more than three years behind schedule—”do not appear to be achievable.”

At the V.C. Summer site near Columbia, S.C., ground was broken for the expansion owned by SCANA Corp. and Santee Cooper in 2011, with the expectation that the first reactors would be online in mid-2016. Current cost estimates for the reactors is 21.6% higher than the original $11.4 billion price tag, and the reactors are now anticipated to come online between April 2020 and December 2020.

Westinghouse is also building four AP1000 reactors at the Sanmen and Haiyang facilities in China, and those projects, too, have been beset by delays ranging from three to four years, mostly owing to design changes.

The Curse of Stone and Webster

Westinghouse’s financial debacle, though, was precipitated by delays at its U.S. projects.

The company signed EPC contracts with owners of the Vogtle expansion in April 2008 and with the owners of the V.C. Summer project in May 2008 as part of a consortium that included CB&I Stone & Webster (S&W), the nuclear construction and integrated service arm of CB&I. Westinghouse was primarily responsible for the design, manufacture, and procurement of the nuclear reactor, steam turbines, and generators, while S&W was to tackle onsite construction and procurement of auxiliary equipment.

The EPC agreements—the first of their kind signed for new U.S. nuclear plant construction in three decades—outlined a “guaranteed substantial completion date” of April 2016 and April 2017 for Vogtle, and April 2016 and January 2017 for V.C. Summer. Significantly, the agreements subjected the consortium to a number of liquidated damages provisions, if it didn’t meet those deadlines.

The projects initially fell off track between 2009 and 2011 when the Nuclear Regulatory Commission requested design changes to the AP1000s related to regulatory changes, including to safeguard the reactors from terror attacks. “These new requirements and safety measures created additional, unanticipated engineering challenges that resulted in increased costs and delays on the U.S. AP1000 Projects and other AP1000 projects worldwide,” Westinghouse explained.

First concrete at the two projects didn’t come to fruition until 2013. Then, as construction progressed, new challenges inevitably emerged. And as the delays compounded, disputes arose between project owners and the consortium about who would bear the ultimate responsibility for cost increases. Vogtle’s owners eventually sued Westinghouse, S&W, and S&W’s parent company, CB&I (formerly Chicago Bridge & Iron Co.). To resolve that litigation, and thwart litigation that could cloud the V.C. Summer project, Westinghouse moved to acquire S&W.

In a major shakeup of contractors involved in both projects, Westinghouse in October 2015 entered into an agreement with Fluor Corp., shifting the primary responsibility for construction to the global engineering firm.

New, Crippling Complications

For both Westinghouse and CB&I, the S&W deal, completed in December 2015, was unavoidable. “[Westinghouse] believed such an acquisition would allow the parties to re-baseline the projects and increase the likelihood of their success,” Westinghouse said.

CB&I, which acquired the Stone and Webster nuclear construction business as part of its $3 billion acquisition of The Shaw Group in 2012, sold it—even though it would incur a $1 billion loss from the transaction—because it provided a “complete end to responsibility or liability” for delays plaguing the Westinghouse AP1000 units.

But for Westinghouse, which acquired the company for a purchase price at closing of $0, the deal has been financially excruciating. Losses, it said, have “accelerated in the past 15 months” following the company’s purchase of CB&I S&W.

Soon after closing the deal, a dispute arose between the two companies rooted in post-closing “true-up” working capital adjustments related to the sale. CB&I claimed it is entitled to $428 million in working capital. However, Westinghouse claimed, using a disputed provision in the agreement, that CB&I owes it $2 billion. CB&I in July 2016 sued Westinghouse in a bid to protect itself from the $2 billion claim.

Meanwhile, Westinghouse entered into settlement agreements with the owners of both AP1000 projects, which resulted in “significant schedule relief,” but hiked up prices associated with the EPC agreements. In the fall of 2016, Westinghouse revealed—following attempts in collaboration with Fluor to quantify construction costs at the projects—that if the reactors were to be built on schedule, at least $3.7 billion in additional labor costs would be needed.

Equipment prices and vendor costs for construction and specific components could drive up costs by another $1.8 billion, it said. Finally, it tacked on another $600 million to cover risk and contingency planning, including warranty and fee claims.

“These preliminary estimates of approximately $6.1 billion could not be sustained by Westinghouse,” the company declared in its bankruptcy filing.

Since early this year, Toshiba and Westinghouse have “explored their limited options” to stay financially viable, even as they continued to face “potentially massive liabilities under the EPC agreements and mounting day-to-day costs at the project sites,” the company said.

If Westinghouse stops work on the AP1000 projects, it would incur “significant damage claims,” in the range of “billions of dollars predicated upon material breach of the EPC Agreements,” it noted.

Left in a Lurch

The future of the U.S. AP1000 projects remains uncertain. Industry observers widely noted that the development raises significant questions regarding Westinghouse’s ability and willingness to physically complete the projects under current arrangements.

Moody’s Investors Service noted the possibility that some risks of nuclear construction and the potential for further cost increases could ultimately shift back to the utilities and their ratepayers. “Although certain Westinghouse obligations have been guaranteed by Toshiba, the value of the guarantee could be diminished by Toshiba’s weakened financial condition,” it said on March 29.

Westinghouse said only that it has reached an agreement with each owner of the U.S. AP1000 projects to continue these projects “during an initial assessment period.”

It added that it “remains committed to its AP1000 technology as the industry’s premier Gen III+ nuclear power plant design, and will continue its existing projects in China as well as pursuit of other potential projects in the future.”

Southern Co., Georgia Power’s parent company, and SCANA Corp. have each issued statements saying they were assessing the situation and exploring their options.

SCANA Corp. said that it has been working with Westinghouse in anticipation of the bankruptcy filing to reach an agreement that would allow for work on the project to continue toward completion of the units. “This agreement with Westinghouse allows progress to continue to be made on-site while we evaluate the most prudent path to take going forward,” said SCANA Chairman and CEO Kevin Marsh on March 29. “Fluor will continue as the construction manager during this period and they continue to work towards completion of the units.”

In an e-mailed statement, Georgia Power spokesman Jacob Hawkins said the company and Vogtle’s other Georgia-based co-owners have also been preparing for the possibility of a Westinghouse bankruptcy filing. ”While we are working with Westinghouse to maintain momentum at the site, we are also currently conducting a full-scale schedule and cost-to-complete assessment to determine what impact Westinghouse’s bankruptcy will have on the project and we will work with the Georgia Public Service Commission and the [c]o-owners to determine the best path forward.”

The company will “continue to take every action available to us to hold Westinghouse and Toshiba accountable for their financial responsibilities under the [EPC] agreement and the parent guarantee,” he said.

The Department of Energy (DOE), which authorized $8.3 billion in federal loan guarantees for the Georgia project, is also watching the situation. “DOE has issued a loan guarantee to one of the stakeholders involved, and for that and other important reasons, we are keenly interested in the bankruptcy proceedings and what they mean for taxpayers and the nation,” DOE spokesperson Lindsey Geisler told POWER.

“Our position with all parties has been consistent and clear: we expect the parties to honor their commitments and reach an agreement that protects taxpayers, promotes economic growth, and strengthens our energy and national security.”

A Storied Legacy

Westinghouse’s collapse is unprecedented in scale and scope within the U.S. nuclear industry, and it could have far-reaching repercussions for entities that are considering nuclear new builds. But it is also a stain on Westinghouse’s storied legacy and solid reputation as an industrial powerhouse.

Westinghouse Electric Co.’s contributions to the power sector are well-documented. The company got its start in 1886 (about four years after the publication of POWER‘s first issue). It was founded by George Westinghouse, whose penchant for invention yielded a transformer that proved to be the key to widespread distribution of electric power.

According to Westinghouse’s website: “His firm faith in the alternating-current system led to the founding of the Westinghouse Electric Company in 1886, which was in bold opposition to the well-entrenched backers of the direct-current system, led by Thomas Edison.” By 1893, Westinghouse had acquired Nicola Tesla’s polyphase system of alternating current and the induction motor, and used it to light the World’s Columbian Exposition at Chicago. The company also won the first contract to install power machinery at Niagara Falls. Reflecting the technology boom, within 10 years of its founding, Westinghouse’s enterprises had grown to employ more than 50,000 workers.

Westinghouse Electric Co. has since steadily bagged a number of power “firsts.” In 1957, it supplied the world’s first commercial pressurized water reactor to the now-decommissioned Shippingport Atomic Power Station in Pennsylvania. About 60 years later, more than 430 nuclear power reactors based on Westinghouse designs are operational worldwide, including at 60% of U.S. nuclear power plants.

But in the 1990s, more than a century after its founding, the company was forced to reinvent itself after a series of financial setbacks. It moved to buy broadcasting company CBS and a number of other broadcasting ventures, renaming itself CBS Corp. in 1997. That year, it also sold its non-nuclear power generation business to German giant Siemens AG.

In 2006, Toshiba Corp. purchased Westinghouse for $5.6 billion in a deal made as the U.S. nuclear sector prepared for a “renaissance” promised by passage of the 2005 Energy Policy Act. The law gave nuclear developers a tax credit package, loan guarantees, and cost-overrun protections.

In 2008, Westinghouse inked deals to build four reactors, two for Southern Corp. at Plant Vogtle in Georgia and two for SCANA Corp. in South Carolina, and regulators moved to approve the nation’s first new nuclear reactors since the 1979 accident at Three Mile Island.

—Sonal Patel, associate editor (@POWERmagazine, @sonalcpatel)