UK Lays Out Fourfold Nuclear Power Expansion in Comprehensive Roadmap

A roadmap released by the UK government on Jan. 11 aimed at quadrupling the country’s nuclear power capacity by 2050 sets out a series of goals and actions that could enable the delivery of 3 GW to 7 GW every five years from 2030 to 2044.

In its 78-page Civil Nuclear Roadmap, the UK lays out a long-term strategy and near-term enabling policies that could propel the country’s ambitions to expand its current 6 GW nuclear capacity to 24 GW, forging a pathway that will both revive its civil nuclear industry and recover its global leadership in the sector. “The purpose of this Roadmap is to send an unambiguous signal to the nuclear sector and investors, setting out how we expect UK nuclear deployment to happen, a timeline for the key decisions and actions, and clarity over the role government and industry should play in supporting and enabling this delivery,” the roadmap says.

The UK government on Thursday also published two consultations. The first, “Approach to siting new nuclear power stations beyond 2025,” begins a process toward designating a new National Policy Statement (NPS) that will apply to nuclear plants deployed after 2025. The effort positions nuclear generation projects as a “critical national priority” in the planning system. The second, “Alternative routes to market for new nuclear projects,” seeks to determine steps the government can take to enable different routes to market for new advanced nuclear technologies.

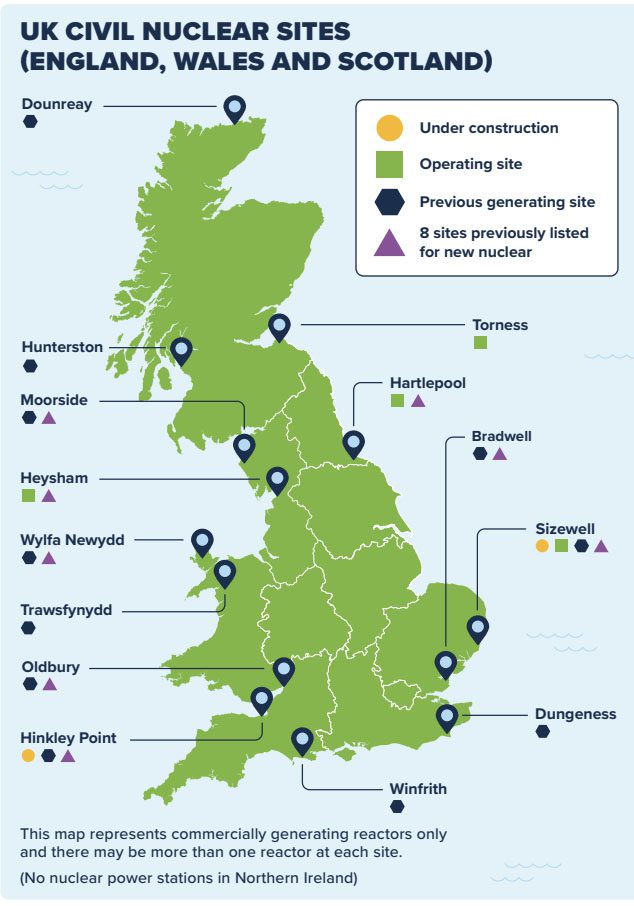

“The proposals will attract investment in the UK nuclear sector by empowering developers to find suitable sites rather than focusing on 8 designated by government,” the UK Department for Energy Security and Net Zero said in a statement. “Community engagement will remain critical to any decisions, alongside maintaining robust criteria such as nearby population densities.”

The government, however, acknowledged that while the roadmap is a substantial step, it does not mark an “endpoint.” The coming years “are also expected to bring further clarity on the costs and effectiveness of new nuclear technology,” the roadmap notes. “This may require us to re-evaluate some of our strategies and policies for the long term. To take account of these developments, we therefore intend to publish a Roadmap ‘update’ by the end of 2025.”

EDF’s $1.6B Investment in Lifetime Extensions

Still, the newly released roadmap marks a major juncture for the UK, which in 2022 moved to “reverse decades of myopia” and established a target to add up to eight new nuclear reactors to its six operational reactors.

Between 2000 and 2023, the UK’s annual share of nuclear power fell from 23% to about 15%. Its current nine-reactor fleet represents a combined power-generating capacity of 6.5 GW. The UK has, meanwhile, partly retired its fleet of second-generation advanced gas-cooled reactors (AGRs) built between 1965 and 1989. The last nuclear plant the nation built was EDF’s 1.2-GW Sizewell B station in Suffolk—the UK’s only pressurized water reactor (PWR)—in 1995.

The country has also long recognized the difficulty of extending the lifetimes of four operational AGR plants for technical reasons. On Jan. 9, however, EDF, a French company that manages the UK’s eight nuclear power station sites, said it plans to invest a further £1.3 billion ($1.66 billion) in five operational sites over 2024 through 2026: Sizewell B, Torness, Heysham 2, Heysham 1, and Hartlepool. EDF said it plans to “maintain output” of the UK’s nuclear fleet of 37.3 TWh until at least 2026. The outlook was improved by life extensions announced in March 2023 for Heysham 1 and Hartlepool (a combined capacity of 2.2 GW) by two years, until at least March 2026, EDF said.

“The ambition is to further extend the lives of the four generating AGR stations, subject to inspections and regulatory approvals,” EDF said. “Heysham 2 and Torness power stations (2.4 GW) are currently due to generate until March 2028,” it noted. “These AGR lifetimes will be reviewed again by the end of 2024 and the ambition is to generate beyond these current forecasts, subject to plant inspections and regulatory approvals.”

EDF also said it is considering a lifetime extension for Sizewell B, a first-of-its-kind single pressurized water reactor (PWR), which is approaching 29 years of operation and could generate power for at least 20 more years. “EDF is investing in the station to allow a final investment decision to be taken on this during 2025.” However, it underscored that “securing a sustainable commercial model is necessary to enable such a decision,” it said.

EDF, notably, is building two EPR reactors at the 3.2-GW Hinkley Point C plant in Somerset, southwest England—the UK’s only nuclear project currently under construction. Hinkley C is slated to be switched on in June 2027. The company has meanwhile proposed a replica EPR project at Sizewell C in Suffolk, eastern England.

In November 2022, the UK government bolstered EDF’s proposal with a £679 million ($815 million) investment, effectively becoming a sizeable shareholder in the project. To date, the government has committed £1.2 billion of investment to support the project’s development. If, as the roadmap suggests, the UK makes a final investment decision (FID) on the power plant by the end of the current Parliament (which culminates in December 2024), Sizewell C could begin operations in the mid-2030s.

Prospects for Large-Scale Nuclear, SMRs, and AMRs

According to the roadmap, the UK government is committed to also exploring another large-scale reactor. “We will set out timelines and process by the end of this Parliament, subject to a [Sizewell C] FID,” it says. “It will be challenging to reach our ambitions without at least the option of further large-scale nuclear projects. Such technologies have been the backbone of the UK energy sector since the 1950s and will continue to be for decades to come,” it notes.

At the same time, the UK is banking on a mass build-out of small modular reactors (SMRs) starting in the mid-2030s and “advanced modular reactors” (AMRs)—which essentially encapsulate Gen IV reactors—for deployment in the 2040s. “By replicating more modular designs, we expect SMRs to reduce the cost of nuclear power. Nuclear projects that are cheaper and lower risk will be more investable and more sustainable as we strive to deliver our ambitions,” the roadmap says. AMRs, meanwhile, can “offer decarbonization capability beyond power provision, including high-grade steam/heat and hydrogen production,” it adds.

As part of the UK’s 2022 British Energy Security Strategy strategy, the country in March 2023 launched Great British Nuclear (GBN). The entity that operates under the government’s repurposed nuclear energy and fuels firm British Nuclear Fuels (BNFL) is tasked with the delivery of new nuclear projects.

But so far, government support for SMRs and AMRs has mostly been investment-based. In December 2022, the government committed up to £60 million to bolster research into high-temperature gas reactors (HTGRs), a technology the UK has historically demonstrated. And in October 2023, GBN unveiled six nuclear designs that will advance to the next phase of the UK’s SMR competition, a fast-track measure that could result in a government contract by summer 2024 as part of a strategy to deliver operational SMRs by the mid-2030s. The next phase of the competition will entail choosing successful technologies that could be ready to enable a final investment decision (FID) by 2029.

In a statement on Thursday, Gwen Parry-Jones, GBN CEO, suggested progress will unfold swiftly. “Since Great British Nuclear started the SMR technical selection process last July, we have moved strongly forward and are on track to complete vendor selection later this year. Shortly we will invite the six companies we have selected to submit tenders,” she said.

The roadmap, however, says the UK will go even further. As part of the Alternative Routes to Market consultation published alongside the roadmap, the government plans to gather evidence “to inform future policy options on how government can support the sector to bring forward investment. We will set out in our consultation response further detail on our ambition to help AMR vendors quickly progress projects,” it says.

Big Decisions Lie Ahead

The roadmap also lays out a timeline for future decisions. “To achieve this ambition, beyond our current commitment to one FID this parliament and two FIDs in the next parliament, we will aim to secure investment decisions to deliver 3-7 GW every five years from 2030 to 2044. This ensures government retains appropriate optionality to achieve 24 GW, while also providing industry the certainty it needs to maximize nuclear replication benefits, especially those of SMRs, where these are deemed value for money,” it says.

The roadmap notes that the 3-7 GW capacity range “is considered the right balance between maintaining flexibility to respond to the needs of the power sector, providing sector confidence, and ensuring a low-cost energy system over the coming decades.”

During the 2030s, it acknowledges, decisions may be needed on projects that could deliver up to 10 GW of nuclear capacity. “As set out, it is likely this capacity will constitute a combination of technologies, across SMRs, AMRs, and large-scale projects. Over time, it will become clear which offers the best value for money and delivery certainty,” it says.

Tackling Long-Standing Barriers, Challenges

The roadmap also sets out how the country will tackle siting and land usage, regulations, workforce development, and financing and funding models—factors that have historically posed hurdles to nuclear development.

Among significant commitments is that the government will seek “a flexible approach” to nuclear siting, though the roadmap acknowledges the approach will be subject to consultations on the new NPS for nuclear. In addition, the roadmap commits the Nuclear Decommissioning Authority (NDA) to periodically publish a prospectus stating which land will be available for reuse. “Where there is commercial interest in available land, the NDA and the government will run fair and transparent processes to lease or option land, with the assumption being that sites go first to new nuclear projects, where that is feasible and represents value for money,” the roadmap says.

The UK, meanwhile, will launch a “smarter regulation challenge” for the power industry. In its Alternative Routes to Market Consultation, the government asked industry to identify how it could reduce “bureaucracy to drive efficiencies in the deployment of new projects.” Other significant commitments include reforms to infrastructure planning and existing environmental assessment processes.

The roadmap also suggests the Office for Nuclear Regulation (ONR) will work to streamline nuclear reactor design assessment and licensing processes for more efficiency and “prepare itself for new market entrants and alternative development models.” As part of that effort, the ONR and the Environment Agency (EA) will “launch a framework for early regulatory engagement for vendors seeking to enter the UK market.” In addition, the agencies will publish guidance to the Generic Design Assessment (GDA)—a non-mandatory regulatory process—“requesting parties on how to maximize the use of overseas regulatory assessment and expectations for moving from a two-step GDA to licensing and permitting.”

Because financing remains one of the most prevalent barriers to the development and deployment of new nuclear—owing to high upfront costs and lengthy construction timeframes—the roadmap lists several efforts the government will take to boost investor confidence. Among them are that the UK will consult on the inclusion of nuclear in the UK Green Taxonomy. “A Green Taxonomy can provide an important tool for enabling the supply of relevant and reliable sustainability information into the market, driving an increase in financing for activities that support the transition to net zero and deliver on UK environmental objectives. It can also support efforts to counter greenwashing and improve market integrity,” the roadmap notes.

As part of yet another commitment, investors and new project developers will be able to engage with the government on the suitability of Contract for Difference (CfD) and Regulated Asset Base (RAB) financing models, the roadmap says. The CfD model, developed to provide support for low-carbon projects like offshore wind, provides investor certainty by providing a fixed price per unit of power. Hinkley Point C, notably, was funded through a CfD, and once it begins generating power, it should receive a “Strike Price of £92.50/MWh (2012 prices) for 35 years, thus providing long-term reassurance to developers and shareholders,” the roadmap notes.

The RAB funding model was introduced by the 2022 Nuclear Energy Act but has been applied to mobilize significant investment in other sectors. It gives eligible companies the right to a “regulated revenue stream throughout the construction, commissioning and operations phase, unlike the CfD which provides revenue only once the power station is generating electricity,” the roadmap explained.

Finally, to further remove potential investment barriers, the UK will seek accession to the Convention on Supplementary Compensation for Nuclear Damage (CSC) to strengthen its Nuclear Third-Party Liability regime. The CSC, which currently has 11 members, establishes an internationally pooled fund that safeguards the interests of potential victims. “This is trailblazing, as we would potentially be the first Paris Convention country to join the CSC,” the roadmap notes. “We have recently taken a key step towards this, having passed legislation in the Energy Act 2023 to enable accession.”

Redeveloping the Fuel Cycle

Along with long-standing barriers, the roadmap addresses future concerns, including how the UK could build out a supportive nuclear fuel cycle, which would both bolster a burgeoning industry and end international dependence on Russia. The roadmap, prominently, commits to “removing any Russian fuel and uranium supply to the UK by 2030 and to working with our international partners to end international dependence on Russia and build shared, resilient allied supply chains.”

The UK acknowledges the measure will require securing supplies of low-enriched uranium (LEU), LEU+ (enriched uranium up to 10% in the fissile isotope U-235), and a UK supply chain for the production of high-assay low-enriched uranium (HALEU, enriched uranium up to <20%). In the roadmap, the UK commits to “establishing full front-end fuel cycle capabilities (conversion, enrichment, deconversion, fabrication) for enriched uranium up to 19.75% by the end of this decade, and to doing this in partnership with industry.”

Earlier this week, notably, the UK became the first European country to launch a program to domestically produce HALEU. Urenco, a UK headquartered international supplier of enriched nuclear materials, recently won an award of more than £9.5 million ($12.1 million ) in “match funding” from the government’s Nuclear Fuel Fund to help develop LEU+ and HALEU enrichment capability at their Capenhurst site in Cheshire.

“We recognize the unique importance of the UK’s two existing nuclear fuel sites, at Capenhurst and Springfelds, in delivering our nuclear ambitions, and that we may need to give particular consideration to the nature of these sites,” the roadmap notes. “We also recognize that we may need to consider whether additional nuclear fuel sites are required.”

As significantly, the roadmap commits to building a geological disposal facility that will be able to accommodate waste from up to 24 GW of nuclear capacity. “A process is well underway to identify a suitable site in which to develop a GDF that has suitable geology and the support of a local community. The first waste is not expected to be placed into a GDF until the 2050s. Until then, there is sufficient interim storage for our legacy waste, waste from our existing nuclear fleet, and waste from currently planned future plants,” it notes.

—Sonal Patel is a POWER senior associate editor (@sonalcpatel, @POWERmagazine).

Updated (Jan.11, 2024, at 5 p.m. CST): Adds details about regulatory, financing, and fuel cycle commitments).