EPA Drops Existing Gas-Fired Plants from Contentious Power Plant GHG Rule

(Updated March 7 with responses from EPA): The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) will drop requirements covering existing natural gas-fired power plants in its final Section 111 rule regulating power sector greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, which is expected in April.

EPA Administrator Michael Regan on Feb. 29 said in a written statement the agency’s rule—which the EPA has sent to the White House Office of Management and Budget (OMB) for interagency review—will instead narrow its focus to existing coal and new gas-fired power plants.

The change is in step with the more than 1.3 million comments the EPA received in response to its May 2023 proposed rule, the agency said. It was also informed by “extensive and productive discussions with many groups of stakeholders to develop effective and workable climate standards that follow the law and are based on available and cost-effective technologies.”

Regan, however, suggested the agency will now work to craft a “new, comprehensive approach” to cover the “entire fleet of natural gas-fired turbines.” While a timeframe for the approach is unclear, Regan said the EPA’s approach may be more stringent, covering “more pollutants including climate, toxic and criteria air pollution.”

EPA Anticipates Three Separate Proposals

On March 7, in response to POWER’s queries, the EPA said it anticipates the “approach” will entail three separate proposals “moving forward in parallel.” The agency suggested the process for the proposals “is to be determined, but regardless of the process, we plan to carry that information forward.”

The proposals include:

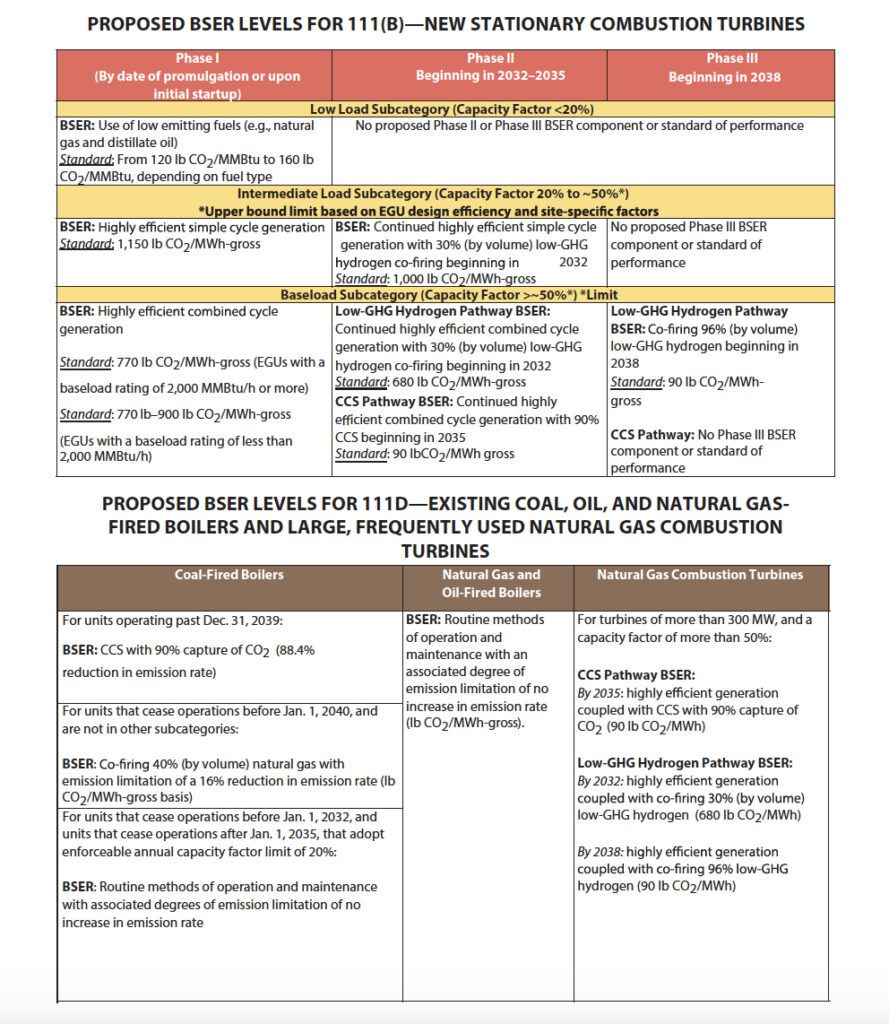

A New Proposal for Emission Guidelines for GHG Emissions From Existing Gas-Fired Power Plants. The EPA’s May 2023 proposal had set out emission guidelines for existing combustion turbines greater than 300 MW that are frequently operated at a capacity factor greater than 50%, setting out a best system of emissions reduction (BSER) that is similar to new stationary combustion turbines—based on either the use of carbon capture and storage (CCS) by 2035 or co-firing of 30% (by volume) low-GHG hydrogen by 2032 (and 96% by 2038).

An Eight-Year Review of the Criteria Pollutant New Source Performance Standards (NSPS) for Combustion Turbines. While its scope remains unclear, this proposal will likely focus on NSPS of stationary combustion turbines outlined under Subpart KKKK, which the EPA issued in 2006. The rule sets a current nitrogen oxide (NOx) emission standard ranging from 15 parts per million (ppm) to 42 ppm for new natural gas turbines. The EPA has issued several other rules addressing criteria pollutants, including Subpart Da—for particulate matter, sulfur dioxide, and NOx—and the recent Good Neighbor Rule. While the EPA first promulgated an NSPS for GHG emissions from new and reconstructed combustion turbines in 2015, the agency’s May 2023 proposal establishes a more protective standard, reflecting the application of CCS and natural gas co-firing. Under the Clean Air Act, an EPA administrator is obligated to review and, if appropriate, revise the standards at least every eight years. In 2022, environmental groups sued the EPA to compel the administrator to perform his “nondiscretionary duty” to review Subpart KKKK and then proposed a consent decree that set a deadline for EPA action by November 2024, with a final rule completed in November 2025.

A Proposed Revision to the National Emission Standards for Hazardous Air Pollutants (NESHAP) for Combustion Turbines—New and Existing Sources. While the EPA promulgated the NESHAP for stationary combustion turbines in March 2004 regulating formaldehyde emissions from new and reconstructed combustion turbines, later in 2004, it finalized a stay for two categories of gas-fired turbines: lean premix gas-fired turbines and new diffusion flame gas turbines. In 2022, the EPA removed the stay on the two categories. The EPA’s forthcoming proposed revision will notably include existing units. In October 2023, the agency suggested 980 turbine units are subject to the combustion turbine NESHAP, mostly at power plants, compressor stations, and chemical plants.

The EPA’s strategic approach to GHG emissions from the power sector presents a “stronger, more durable approach” that would achieve greater emissions reductions than the current proposal. Significantly, it will also “consider flexibilities to support grid operators and will recognize that ongoing technological innovation offers a wide range of decarbonization options,” Regan said.

Regan said the EPA will “immediately begin a robust stakeholder engagement process, working with workers, communities with environmental justice concerns, and all interested parties to help create a more durable, flexible, and affordable proposal that protects public health and the environment.”

Asked about whether the agency would delay the proposals until after the November election, as many news outlets have conjectured, the EPA on Thursday said that engagement has already begun and will continue for the next several months as the EPA develops its proposals. “We will be sharing more details soon,” it said.

A Contentious Rule

As POWER has reported, the power industry has fiercely pushed back against the EPA’s May 2023 proposal, which set new carbon pollution standards for new gas-fired combustion turbines; existing coal, oil, and gas-fired steam generating units; and specific gas-fired combustion turbines.

A key concern voiced by the industry in thousands of comments is that the emission reduction requirements would be achieved through performance standards, reflected through the application of the best system of emission reduction (BSER). BSER, however, is based on EPA’s predictions regarding the future availability and capacity of various technologies, including carbon capture and sequestration (CCS) and hydrogen co-firing.

While the proposed rule requires power-generating units to meet the standards in phases between 2024 and 2038, the power industry has cited practical misgivings, including technology gaps, technical limitations, and, prominently, that clean hydrogen’s production and availability are currently severely limited.

In November 2023, the EPA released a supplemental proposal, seeking comment on whether to include mechanisms to address potential reliability issues with respect to the agency’s Section 111 rules. That proposal also received thousands more comments before Dec. 20, 2023, when the public comment period ended.

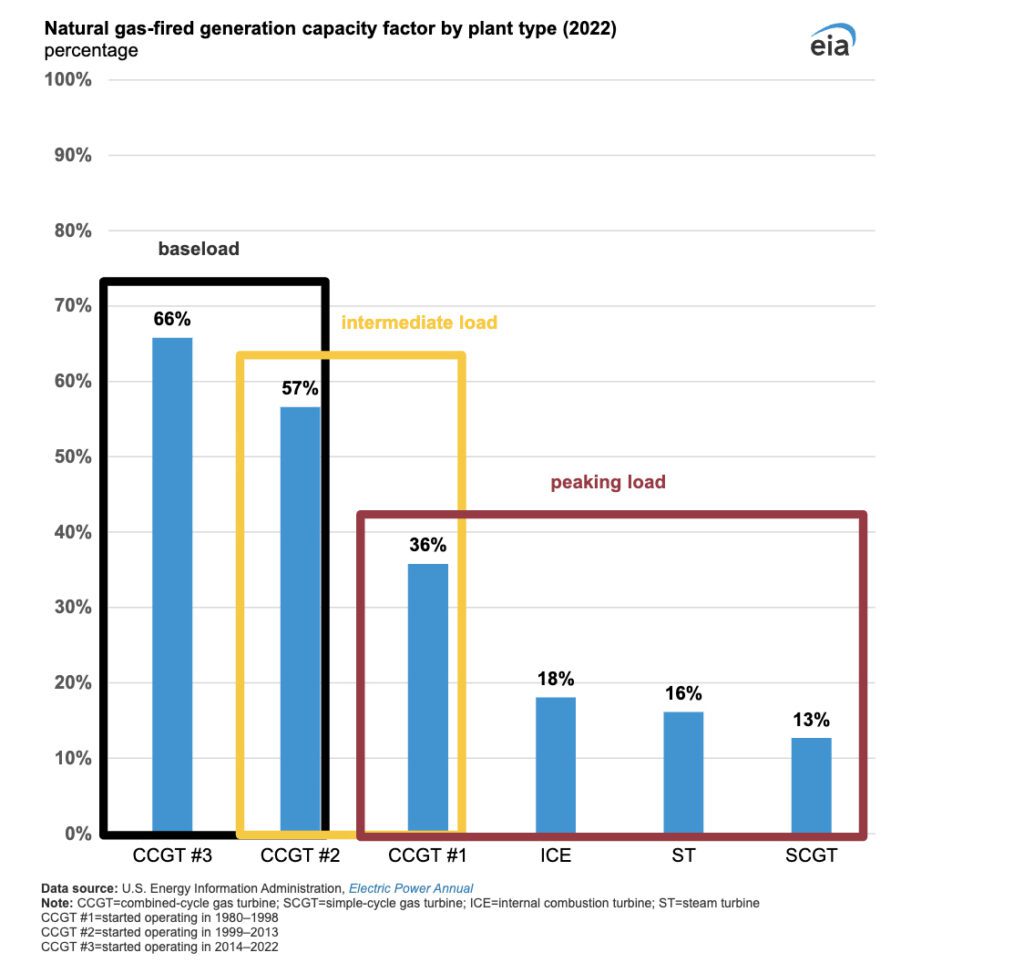

Gas Power’s Most Valued Attribute: Dispatchability

At the heart of the issue is that nearly all natural gas-fired power plants in the U.S. are dispatchable, “meaning that they can be reliably called on to meet power demand when needed by the grid,” the Energy Information Administration (EIA) explained recently. The U.S. gas power fleet today generates about 43% of the nation’s power—a combined 1,802 TWh in 2023—more than any other generating source in the U.S. Today, the gas power fleet is dominated (58%) by combined-cycle gas turbines (CCGT), though simple-cycle gas turbines comprise another hefty 26%, followed by steam turbines (15%) and internal combustion engines (ICE).

Dispatchability has grown into a critical attribute as the nation’s grid profile shifts in response to multiple factors. Experts have repeatedly highlighted a paramount urgency for adequate flexibility as concerns about system reliability mount.

Grid operators bluntly told the EPA in response to its May 2023 proposal that the rule would have an incremental impact on bulk power system reliability, highlighting concerns about the investment in generation needed to maintain reliability. The Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT), the Midcontinent Independent System Operator (MISO), PJM Interconnection (PJM), and the Southwest Power Pool (SPP) also outlined, with veracity, concerns about EPA’s proposed timelines for the GHG power plant rule and provisions that could accelerate the pace of dispatchable generation retirements.

The group noted several other EPA power plant rules, including the Effluent Limitations Guidelines and the Coal Combustion Residuals Rule, have had an effect on accelerated retirements, though the EPA included mechanisms to mitigate some of that impact. Last year, the EPA also issued the final “Good Neighbor Plan,” its latest iteration of the Cross-State Air Pollution Rule (CSAPR), a rule the EPA projected would result in an additional 14 GW of coal retirements nationwide.

“States that have restructured their electricity markets have effectively ceded their ability to order new generation. Rather, they depend on the market to send price signals to attract new generation and retire unneeded generation,” the grid operators said. “The markets have worked quite well in achieving that goal.”

In PJM, during the Mercury and Air Toxics Standard (MATS) rule transition, the market “efficiently replaced 20,000 MW of coal generation with new, cleaner, natural gas generation that took advantage of the shale gas revolution that was occurring simultaneously,” the grid operators noted. “However, as PJM detailed in its 4R’s (Resource Retirements, Replacements and Risks) Report, the markets cannot instantly replace policy-driven unit retirements with units that provide the same or even enhanced reliability services.”

Last week, MISO, in its updated Reliability Imperative report, underscored a similar point, suggesting the GHG power plant proposal added another wildcard to an already “hyper-complex risk environment.” If EPA’s proposed rule drives “coal and gas resources to retire before enough replacement capacity is built with the critical attributes the system needs, grid reliability will be compromised,” MISO starkly warned. “The proposed rule may also have a chilling effect on attracting the capital investment needed to build new dispatchable resources.”

Trade groups have also urged the EPA to be more vigilant about reliability and investment impacts. “Reliability tools and mechanisms should be included in the Final 111 Rules and should be focused on the particular challenges that arise from the structure of those Rules. In its simplest form, this means that EPA should provide paths to compliance with GHG emissions limitations for units whose operations may be essential for the reliability of the energy grid,” the Edison Electric Institute, a trade group that represents all investor-owned utilities in the U.S., wrote in its last round of comments submitted in December.

“To accomplish this, EPA may need to provide more flexibility to amend state compliance plans to allow units to change compliance pathways more easily and efficiently. EPA also may need to create a process whereby grid reliability experts can provide input to EPA about potential challenges in support of requests for compliance flexibility for reliability-critical units,” it said.

CCS, Hydrogen Deployment Is Lagging

The power industry’s most prevalent concern, however, rests on the EPA’s seemingly tone-deaf optimism that the technology it champions as BSER will be commercially available to temper GHG emissions by 2032.

In August, EPRI, an independent, nonprofit organization for public-interest energy and environmental research, laid it out starkly: “The combined effects of the proposed rules would impact approximately 40% of total U.S. dispatchable power generation capacity,” it said. But, “The emerging technologies identified in the rules—CCS and hydrogen—have seen little to no deployment at scale so far and depend on new infrastructure with impacts to project timelines, feasibility, and costs beyond the scope of EPA’s analysis,” EPRI said.

Although the proposed rules treat CCS and hydrogen similarly, “they are two very different technologies that are not comparable in their GHG reduction impacts or timelines to scale,” EPRI underscored. “These emerging resources require entire new supporting infrastructure (that is, production, pipelines, and storage for hydrogen; pipelines and storage for CCS), and should be considered in their entirety to fully understand the potential benefits, costs, and deployment challenges and opportunities.”

In addition, EPRI urged the EPA to consider overall emissions impacts from system changes resulting from retirements of existing coal- and gas-fired power plants, additions of variable renewables (such as wind and solar power), and changes in load profiles from electrification. The changes are already underway but may be amplified by Infrastructure Reduction Act incentives, and proposed performance standards may alter the operational profile of the remaining dispatchable generation fleet, it said.

“Engaging in these types of flexible operations more frequently may lead to accelerated degradation, impacts on efficiency, and reductions in plant reliability. For instance, EPRI research illustrates the extent of efficiency losses associated with load following and identifies portions of the plant that are impacted most by decreased load stability,” it added. “Such operational regimes and their contributions toward lowering total CO2 and integrating renewables may mean that emissions intensities (in mass of emissions per MWh of electricity generated) may increase even while total emissions fall. These factors may also impact assessments of resource adequacy and operational reliability.”

A Broad Array of Criticism and Reactions

The Biden administration’s GHG power plant rule, meanwhile, has also attracted intense scrutiny from lawmakers, mostly Republicans. In December, Senators John Barrasso (R-Wyoming) and Shelley Capito (R-Wyoming), members of the Senate Energy and Natural Resources (ENR) Committee, urged the EPA to rescind the rule, which lawmakers are calling “Clean Power Plan 2.0.”

“We are deeply concerned that the Agency’s proposal is unachievable, uneconomic, and unreasonable for small and large electric generating units (EGUs) alike given that the emissions control technologies mandated are currently inadequately demonstrated,” they wrote. “Further, the proposed Clean Power Plan 2.0 fails to sufficiently consider the serious reliability concerns already raised by stakeholders, regulators, and independent experts.”

The EPA’s announcement on Thursday predictably elicited strong reactions. Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse (D-Rhode Island), a vocal climate advocate, blasted the EPA’s approach. “Making a rule that applies only to coal, which is dying out on its own, and to new gas power plants that are not yet built, is not how we are going to reach climate safety. Failing to cover the plants responsible for the vast majority of future carbon pollution from the power sector makes no sense,” he said. “It is inexplicable that EPA, knowing of these emissions, did not focus this rulemaking on existing gas-fired plants from its inception.”

The Clean Air Task Force (CATF), which calls itself a “pragmatic, non-ideological advocacy group” dedicated to serving climate change, also voiced disappointment. CATF, in comments to the EPA, had recommended even more stringent requirements for gas power. It urged expanded coverage of a CCS-based emission limit on existing gas-fired plants to those with capacity above 600 MW and total capacity utilization of more than 45%. “Making that change would increase the emissions covered by combined cycle units by 78% over the proposal while increasing the number of covered plants by only 30%. EPA already has the information it needs in the record to support the finalization of an existing gas standard,” it said.

CATF, however, recently told POWER that CCS, including for coal and gas power, faces cost limitations. Carbon capture, meanwhile, may not be suitable for all fossil fuel generation, and its impact on plant performance remains a concern.

On Thursday, CATF attorney Frank Sturges said, “While the standards on new gas plants and existing coal plants are a welcome step in the right direction, alone they are not enough.” Sturges noted that the EPA’s Science Advisory Board last week found that GHG reductions from EPA’s proposed suite of power plant regulations—including existing natural gas plants—are insufficient to meet the U.S. national climate goals and could be strengthened by doing more on existing natural gas plants. Not finalizing existing gas standards this spring “risks a significant shift in generation and emissions from existing coal plants to existing gas plants,” he said. “EPA can and should finalize an emissions standard that covers a broader swath of existing gas plants, not just a few.”

—Sonal Patel is a POWER senior associate editor (@sonalcpatel, @POWERmagazine).

Editor’s Note: This story was originally published on Feb. 29. Updates include details from the EPA about the timing, scope, and details of its proposed approach.